Cézanne and Mystical Threads of Creative Genius

Evidence of interplay among the giants of art, science, and literature. Or, how to fill an August afternoon pre-apéro hour.

" When you're born there, it's hopeless, nothing else is good enough."

- Paul Cézanne (referring to Aix-en-Provence.)

Cézanne is THE son of this city. Other great artists have called it home (Émile Zola and Bill Magill, as fine examples), but none attained the level of acclaim and continued adoration of our good friend Paul. And for that he’s being celebrated this summer with exhibits and events in Aix.

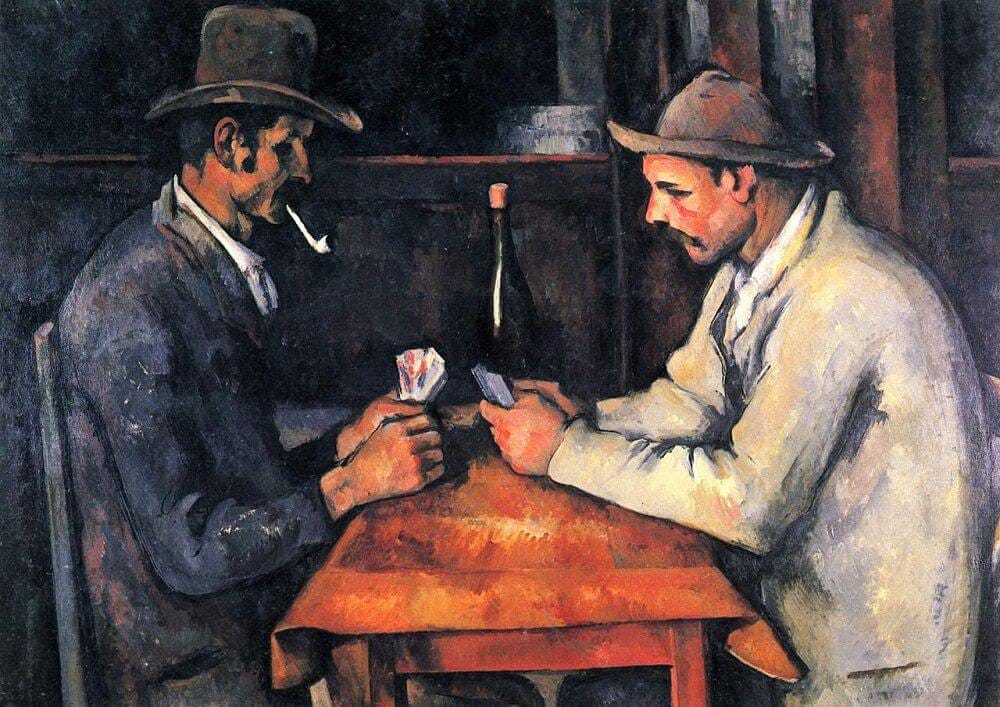

I’ve often considered Cézanne’s peerless renown over my years in Aix, tracing his steps through town (the favorite haunts are marked with sidewalk-embedded badges) and lingering over his works in the modest, local Musée Granet. In 2012, the royals from Qatar paid north of $250 million for his The Card Players, making it the world’s most valuable painting at the time. (Did they realise he painted 3 versions? Suckers!)

My appreciation of art is recreational at best. I do like Cézanne, but love Van Gogh. Vincent, too, tumbled hard for the soft yet vivid hues of Provence, doing his most celebrated works in Arles (the ear cutting) and Saint-Rémy (the asylum sleeping). Maybe it’s the drama queen in me that is roused so deeply by the hallucinatory Starry Night, painted before a summer sunrise in 1889 from his asylum window.

A tortured artist Cézanne was not, but radically trailblazing, and considered the creative leap through which impressionist water lilies met cubist taureaux. Picasso and Matisse are both said to have called him “the father of us all,” and the English curator Lawrence Gowing submits that Cézanne’s daring work with the knife pallet introduced “the idea of art as emotional ejaculation.” (I’m committing that phrase to memory.)

But this isn’t an essay about one man’s genius.

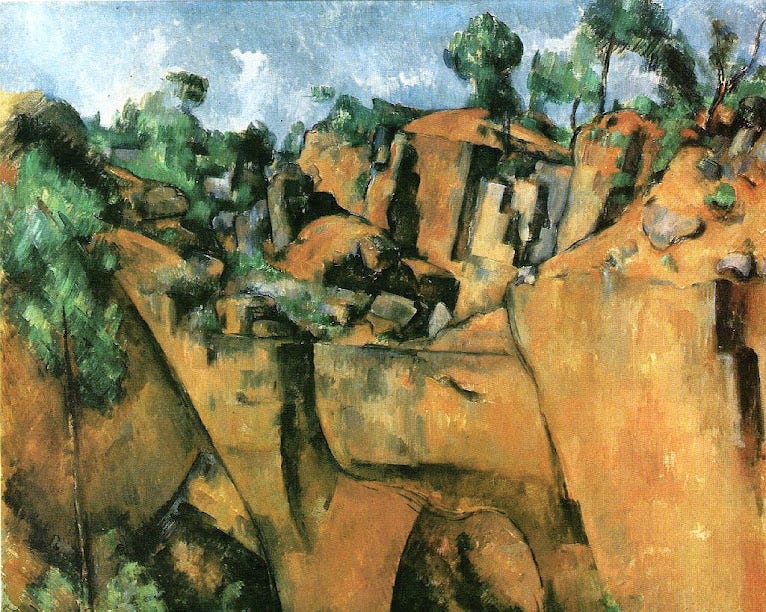

What I find most fascinating about Cézanne’s story is not his meteoric impact on 19th century art, but the spooky threads of style and concept that connect this artistic evolution to his trailblazing contemporaries in other disciplines of the same period, such as literature, music, science, mathematics, and dance.

An argument can be made – and ChatGPT makes it here more succinctly than me – that the creative pioneers of this period shared Cézanne’s obsession with:

Subjectivity and perception. Cézanne wasn’t just painting what he saw, but how he perceived the subject of his gaze.

Fragmentation and reconstruction. He broke forms first into geometric shapes, and then reconstructed them wholly reimagined on canvas.

The essence of things. Cézanne placed a higher emphasis on the underlying essence of objects than the mere surface appearances.

And so I prompted my trusted assistant further to offer examples that amplify my Wednesday afternoon art-of-distraction epiphany of inspired interdisciplinary connections. And this they/them told me:

On literature, “Marcel Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time’ is almost exactly the literary equivalent of Cézanne. He broke from traditional narrative structures and focused on subjective experience, memory, and the reconstruction of reality through fragments of sensory detail.”

On music, “Claude Debussy moved away from traditional harmonic structures in music. Like Cézanne, Debussy was creating atmosphere and evoking emotions through suggestion rather than direct statement.”

Listen to Rêverie, by Debussy:

On philosophy, “Henri Bergson's philosophy of duration aligns with Cézanne's attempt to capture the essence of objects over time and through multiple perspectives. He emphasized intuition and subjective experience as ways of knowing the world.”

On dance, “Isadora Duncan rejected the rigid formality of classical ballet, seeking a more natural and expressive form of movement. She was after something real and less contrived, as was Cézanne.” Watch Duncan dance here.

Additionally, math and science became increasingly abstract through the 19th century, with the introduction of complex numbers and the theory of entropy, holding that every system in the universe inevitably trends toward disorganized states. (One look at my son Shane’s bedroom, during his teenage bedlam years, was convincing proof that the theory of entropy was holding up well.)

But this isn’t even an essay about spooky threads in a temporal creative plane. This is a meandering stream-of-consciousness lazy summer arc about the much-debated merits of higher education in 2025. Stay with me, we’re almost done.

At the University of California, Davis I studied physics (major #1) and economics (major #2), to which I pivoted after making first contact with the mental horsepower required to complete major #1. (Also, the hottest girls on campus were on the liberal arts side of the Quad.) Davis was a fantastic school with an amazing faculty, and I learned a lot in both departments. But it wasn’t the core courses that marked me most deeply, nor made me a more interesting Bill. It was in the wildly obtuse electives in which I chose to enroll: Altered States of Consciousness; Mexican History; Film Appreciation, Wine Tasting, and (most relevant to this essay) a course that extended the oft-discussed creative parallels between Picasso and Stravinsky to the works of Max Plank, Sigmund Freud, Samuel Beckett, Alberto Giacometti, and John Cage. This course blew . my . fucking . mind. As my expressive friend and author Mike Finkel is known to exclaim: BOOM!

You may see where I’m going here. Without this Davis course my recent Wednesday afternoon - pre-apéro - would not have been wasted noodling on Cézanne’s threading connections. For that matter, without my university immersion I’d be ill suited to pontificate on the significance of Casablanca in the larger pantheon of Hollywood films, or explain the improbable success of Cortez and his band of 500 conquistadors in wrestling control of Tenochtitlan from Montezuma and his immense Aztec army, or (and this is my favorite) introducing my son Jess to the concept of lucid dreaming as a child. Fascinated with the concept of controlling his own dreams, Jess threw his teenage self into mastering the skill (should it truly exist).

Not everyone needs a 4-year university education. Shane is finishing up his second trade school degree now, happy as a clam, and fully employed. But the admonition of higher education, mostly by bloviating billionaires like Musk, Thiel, and Altman, completely misses the mark. Yes, ALL institutions should be in constant states of evaluation and reform, but a university’s greatest value is not in preparing you to maximize income, it’s about seeding your curiosity in unexplored areas that will render you a more interesting and engaging person, and through that elevation, a more creative contributor to society writ large (or writ small, with your apéro friends on any given August afternoon).

It’s rosé hour. Talk soon.